By MarisaWith the bike not starting from our ride through Bolivia's salt flats, we were in a bit of a predicament. Our dear and wonderful friends who'd stayed by our sides throughout it all, Brendon and Kira Hak, were on the verge of overextending their visa in Bolivia, and needed to go. Unlike us, their bike was fully functional, and their plan was to take a difficult, but gorgeous route south and out of Bolivia: the Lagunas Route. But as Tim and I found ourselves immobile in the town of Uyuni, we knew that if we didn't get our bike running before they had to leave, we would not want to do such a challenging road by ourselves with a questionable motorcycle. Our plans and dreams of riding the Lagunas Route were now falling apart. So the pressure was on for Tim to fix the bike, and he needed to do it by 11:00 AM the next day, which was checkout time for the Haks and the latest possible moment before they had to leave. Tim had not properly slept for days, just thinking about the bike and what could be wrong with it. We knew that riding it out into the wet salt flats was a big risk (though we got some incredible pictures out there), but I'm not sure we realized quite how detrimental it would be for our motorcycle. Salt is not just corrosive to metals, but electricity also speeds up its corrosive powers, making it erode anything electrical as well. With a big bike like ours, most of its functions are run through the motorcycle's CPU, and that means that nearly everything, from the tire pressure gauge to the suspension, are electronically controlled. Though we washed the bike again and again, salt could've gotten anywhere, and eaten away at any electrical component. Thankfully, Brendon helped Tim out every waking moment he could, and they narrowed the problem back down to the kickstand, which was their original suspicion. Yup, even the kickstand has an electronic sensor that doesn't allow the bike to run or go into first gear when the kickstand's down. Though the faulty kickstand's symptoms seemed more similar to a fuel issue, it was the wiring harness to this tiny sensor that the salt had destroyed: the culprit of all our woes. So only two hours before the Haks were supposed to leave, Tim and I were running around town, trying to find a tiny electrical resistor to bypass the kickstand sensor. And after wandering around for an hour and a half, we had just a half hour left when we finally found it! Tim ran back to the hotel where the bike was, he and Brendon installed it, and it worked! We were stressed, exhausted, but ecstatic. With truly no time to spare, at least we had a functioning bike once again, and could finally go with the Haks on the Lagunas Route! We packed up, got gas, wolfed down some food, and with big smiles, we headed out to conquer one of the worst roads in Bolivia. The Lagunas Route is known to be a difficult road, especially for large motorcycles or drivers of any vehicle without 4WD. It's usually only taken by local Jeeps and off-road vehicles looking to bring tourists on a sight-seeing journey through southern Bolivia and into northern Chile. There are a couple of isolated hotels situated along the way that have sprung up due to the tourism, but there are no gas stations, towns, restaurants, or any other type of amenities. It's rugged, cold, beautiful, and the very essence of the word adventure. The Lagunas Route isn't actually one road either, but there are several ways to go. The eastern side is said to be easier, but only because it has less deep sand. But the western side is known to be more picturesque and the way the tour groups go. So regardless of the poor road conditions, with the Haks and a working bike, we now felt invincible. So we knew that west was the way we wanted to take. We began by camping near the last real outpost, a town called Culpina K, where we stocked up with several days' worth of food, water, and as much gasoline as we could possibly carry. The next day was easy going until we turned off the main gravel road, and headed south into the real Lagunas Route. The road started ascending, and turned into a rutted and gutted channel filled with large rocks. It was definitely a high-clearance vehicle road, but Tim did an expert job of getting us safely up and into the high-elevation altiplano where we found ourselves in a flattened plain surrounded by snow-capped mountains. From there we rode along what would become the norm for the next few days: sandy washboard. It's not difficult riding, but the bumpy corrugation was very uncomfortable, plus it's terrible for the bike. But all we cared about at this point was that we were running, staying upright, and on the Lagunas Route with our friends. And then we saw our first laguna: a clear shallow body of water filled with flamingoes. And this is part of the reason why people come out here on these horrible roads, to see the threatened Chilean flamingoes in all their soft-pink glory. When these massive birds “graze" for plankton with their bills upside-down in the water, they make this pleasant clucking and chirping sound to each other. And when they fly with neck and spindly legs outstretched, flapping those pink and black wings, they look more elegant than I ever thought a flamingo could. It was very special to see such wild and precious animals right in front of me. We camped next to a hidden lagoon of flamingoes with no one else around in what I considered to be extremely barren and hostile terrain. The sun and wind up at that altitude was intense (14,000 ft / 4,250 meters), and we found our faces and lips were immediately chaffed. Even my fingers around my nails got so dry, some started bleeding. Surrounding us were massive mountains and volcanic rocks encasing the lagoons of strange sulfury colors, so the only signs of life were dry tufts of grass, and then these gorgeous tropical-looking pink birds. The flamingoes just seemed so strangely at peace within their lunar world, and so out of place. What's more, we'd read that every night, the water that the flamingoes stand in freezes over (it's very cold up there, and this time of year is summer!). And then in the morning they're stuck until it thaws and they can move around again. For me, it felt like a very bizarre new planet up there in the far-flung reaches of Bolivia. Day two was going to be the hardest day, but also with the most sights to see. We started off in the morning only to be jostled about as we made our way down the washboard road for hours, and had to take frequent picnic stops to rest our rattled bones and brains. The whole time, there were tour-group Jeeps speeding around us, avoiding the terrible roads by cutting through the flat areas and making new roads of their own. It was weird being out in the middle of nowhere, and at the same time surrounded by so many people from around the world. After successfully navigating through another bout of ruts and rocks in a narrow ravine, we bumped our way along windswept valleys of sand between colorful mountains. The terrain became more and more desert-like the further south we went, and we passed lagoon after lagoon, which were like pockets of pink and blue life amidst the reds and grays of the rocky wilds. For lunch we stopped near a red outcropping where a few of Bolivia's rodent chinchillas came out for a photoshoot. They're locally called viscachas, and though they resemble fat fluffy rabbits, they have long fuzzy squirrel-like tails, and hilariously lazy eyes with droopy eyelids. One of the main photo stops of the Lagunas Route is the Rock Tree, or Árbol de Piedra. It's just a rock that's in an interesting shape, but it's surprisingly big, and also surrounded by other strange stones carved into pocked and rounded shapes by the intense wind. Unfortunately, this is where Brendon started noticing a strange crunching noise coming from his front tire. After a bit of inspection, the diagnosis was not looking good, as it seemed there was something majorly wrong, though nobody could be sure of what without taking everything apart. And we had a long way to go before reaching our campsite that night near Laguna Colorada. So we slowly made our way onwards and hit the worst stretch of sand of the whole trip. This was deep sand, and it was visibly impossible to distinguish from the not-so-deep-and-horrible sand. You just came upon it, the tires would want to slip out from underneath, and then you'd do your best to stay upright. It was slow wobbly going, and Tim and I fell a few times (ok, five times). The Haks of course did not fall at all, though they almost did, and they are superhero off-road pros. I would not recommend this stretch of road to anybody on a large and heavy motorcycle. By the time we got to the national park checkpoint at Laguna Colorada (where we had to pay 150 Bolivianos per person to enter: ~$22), we were simply beat and tired. Once getting our tickets, we passed the ambers, blues, and whites of Laguna Colorada and the hot-spring pools next to it where people were soaking and enjoying the volcanic warmth, but we were in no mood to stop needlessly. The Haks' bike was sounding worse and worse, and we knew we needed to get to camp before we could rest and see what was wrong. That night we camped in an isolated canyon near Laguna Colorada, and though the temperatures were icy cold at night, this camp spot was like a paradise for me. I love reddened deserts of sand, silence, and stars, and I found the canyon to be glittered at night in some of the most impressive star-scapes I've ever seen. The third day was to be our last day on the Lagunas Route, and the day we'd cross into Chile. But we had some major challenges ahead of us. We were running low on gas and food, but what's more, after taking the front assembly apart on Brendon's bike, he discovered that the bearings had become shredded apart like a bomb had blown up inside. We'd heard from a mechanic back at the salt flats that this is a common problem with bikes that go into the salt, as it eats away at the grease in the bearings until the balls become dry and macerated like shrapnel. But as we were in the middle of nowhere, and this was the last day on the Haks' visa for Bolivia, there was nothing else to do but just keep going. At a very slow pace, of course. And without front brakes. Even using the back brakes didn't seem to be a good idea for the Haks, but luckily, the road was flat that day. And so we limped ourselves along to the Sol de la Mañana Geysers, just off the main path, and it was an extraordinary sight to see the wafts of sulfur steam drifting out of mud pits and caverns in the colorful earth. It seemed to be a suitable end to this bizarre and magnificent world of southern Bolivia. We crawled past Laguna Blanca and the impressive conical volcano of Lincancabur, and finally found ourselves at the Chilean border, where I saw something strange in the distance. Could it be pavement? And white and yellow lines, and a speed limit sign, and little reflector thingies? I hadn't seen such safety standards in so long, I couldn't be sure, but as the bike's tires mounted the smooth surface of the asphalt, I breathed in a sigh of comfort. No more Lagunas Route. It had been incredible, but at that moment, I was glad for no more rocks and ruts and jostling around. But the comfort didn't last long, because this border with Chile may have been the windiest border I've ever been to. It was brutal up there, and the wind cut straight to the bone through my layers of jackets. But as we entered Chile's customs office, we found ourselves in a room with computers, leather chairs, cameras on the ceiling, and even a heater! I couldn't believe the modernity around me. And as the officer handed me a pen to fill out a form, I found my hand was too cold to write anything, and I just stared at his crisply-ironed uniform as Bruno Mars played in the background, and I thought, “Have I died and gone back to America?" Kira and I looked at each other, both faces red from sunburn and with flaky skin, and I noticed that bits of moisture around our watery eyes and running noses had dried into white crusts. We looked like we had just been through the pits of hell, and certainly did not belong in this clean room of new things. And I said through lips so chapped they hurt to move, “After four months of being in Peru and Bolivia, if this is what Chile's like, I don't know if I can handle all this niceness." And I don't think we were ready at all for the first-world challenge that is Chile. Rules and laws and paperwork and such. Because as they searched our belongings and found some sparklers that we had leftover from New Years, it started to sink in that I am not in Bolivia anymore. Bolivia is a country where you can chew coca leaves all day long and buy dynamite and set it off wherever you want. But apparently Chile is a whole other world. And as they threatened to handcuff Brendon for trying to smuggle pyrotechnics over the border, I realized that we had done something illegal, and that this was bad. Thankfully, the police officer did not seem excited to arrest Brendon, and as we all pleaded that we had no idea about the laws and were just lowly miserable travelers with no gas and broken-down bikes and salt still seeped into our clothes with nothing else to eat but day-old rice, they tore up the sparklers and said, “We'll pretend these never existed." Thank God! It was 47 kilometers (30 miles) to the next gas station in San Pedro de Atacama, and Tim and I were on empty. We were below empty actually, at the flashing lights point. And we were more than worried that even after all we'd been through, we might not ever get there. But as we left the custom's office and rounded a turn in the road, the sun broke out from the clouds to reveal an illuminated valley below us where San Pedro de Atacama was. And as if the light and warmth were guiding the way, we coasted down the perfect pavement, not even hitting the gas, picking up speed with the dive. The engine could've even been off. And after countless ear pops and 6,700 feet of descent in elevation (2,000 meters), we arrived in San Pedro elated that we had somehow made it through the Lagunas Route. So here we are in San Pedro de Atacama in Chile, an incredibly expensive town compared to what we're used to in Peru and Bolivia (our hotel costs us $44 a night!). But it's a beautiful, fun, sunny place full of energy, adobe walls, tourists from around the world, and even some amenities for our bikes. And there are addresses here, and mail! Which means that Brendon and Tim are currently waiting for parts to arrive from Santiago, because we've decided that whatever the Haks need to do to their bike due to the salt, we should probably do the same. And so as we wait, we're relaxing here with fellow motorcycle friends that we've made along our journey, recuperating until our next adventure. And what's next? We're not sure, maybe the desert canyons of northern Argentina? But whatever it is, we'll keep the stories, pictures, and videos coming. For our latest updates and images, check us out on facebook and instagram. The Gear We Carry |

Follow UsRide with us from Chicago to Panama!

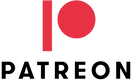

2Up and Overloaded Get inspired by the tale that started it all:

Maiden Voyage 20 author's tales of exploring the world!

The Moment Collectors Help us get 40 miles further down the road with a gallon of gas!

Become a Patron for early access to our YouTube Videos!

Subscribe to our YouTube Channel!

Subscribe to our Blog by Email

|

2Up and Overloaded

Join our clan of like-minded adventurers...

Proudly powered by Weebly

Designed by Marisa Notier