By MarisaYes, it looks awesome: the mirror effect of the largest salt flats in the world during the wet season. But don't let the surreal image of us riding through the Salar de Uyuni in Bolivia fool you, because it has rendered our motorcycle immobile. The amazing photographers who took this shot are our friends Kira and Brendon Hak, the fellow KTM-riding duo called the Adventure Haks. We met up with them for Christmas in Sucre, Bolivia, and then headed south together a few days before this epic failure-of-a-ride. Before we got to the salt flats, we made a brief stop in Potosí, a high-altitude historic city with a very rich silver mine next to it. In fact, the mine was so lucrative in the time of the Spanish (and still produces plenty of ore), that mining towns in Mexico, Wisconsin, Missouri, and Nevada have been named after Potosí in the hopes of producing similar wealth. Though most tourists who visit Potosí take a tour of the mine, I had a stomach bug and chose not to go. But I'm not sure how much I would've liked seeing the conditions of the workers there, since I've heard it's somewhat horrific. Luckily, the colonial center of Potosí itself turned out to be very quaint, and it was nice to walk around the pedestrian-only streets at night lit by old lamps. It almost reminded me of Paris. Ok, maybe that's a stretch, but it was nice. After Potosí, we headed straight to Uyuni, the town that is the jumping-off point for the salt flats. We camped the night at an old train yard full of rusting engines and train cars half-buried in the sand. At first I thought this place would be boring, but it turned into a unique and fascinating experience as we cooked our dinner atop one of the cars, watched the sun set over the vast desert, and then slept beside the silence of the long-retired trains. It was like we were in the Bolivian version of the Wild West. Finally, it was New Year's Eve, and the day we'd been waiting for: our venture into the salt flats. We had heard that just the week prior, the Salar (salt flats) was as dry as a bone, but that recent rains had turned some areas into the mirror-like effect we had been hoping for. So we washed our bikes with diesel grease for a protectant (because we knew that salt was bad for our bikes, we just didn't realize how bad), and then headed out. After a brief stop at the Dakar Rally sign, we were soon in the vast nothingness of the salt. It's almost dizzying to see just white and sky around you, and it was hard to follow the GPS that wanted to take us down certain “roads". So we finally decided to just pick a point on the horizon, and head that way. Things started out hard and dry, but as we headed deeper into the flats, we noticed a layer of slush forming on the surface. Even though some parts looked mushy, we were pleased to find that salt is sharp, and our tires could easily grip onto it. And then all of a sudden we were in the mirror, and it surrounded us like infinity. It was like we were transported into the clouds and even beyond, into a glassy version of outer space. It was hard to tell where the land began and the sky ended, and it felt like we were floating in oblivion, skating through a dream of ice and clouds, or simply soaring through endlessness. It was a truly magical experience that I wish I could recommend to all. Unfortunately, we are currently not sure if this all turned out to be worth it. We spent a long time out there in the mirrored abyss, jumping, skipping, doing cartwheels, driving in circles, and all the while snapping pictures like we never wanted the dream to end. If I had ever stepped into the looking glass and ended up in Wonderland, then this was it. But, as with all dreams, this too had to come to an end. We knew the salt water could not be good for our bikes, and we could see it already crystalizing over the engine. In fact, as we rode further through the mirror, Brendon pulled us over to tell us that our exhaust pipe had completely crystalized over in salt. And sure enough, it had. We had to pick it apart with pliers, and then realized that the exhaust pipe was even coated with salt on the inside. Though we had originally wanted to camp on one of the “islands" in the Salar, we realized that more importantly we needed to get our bikes out of the salt and washed. And it needed to be done soon. So we headed to the closest dry land, first having to ride our bikes through deep puddles of salt water where buses and Land Rovers had dug trenches with their tires. It almost makes me cringe to write this, but I was knee-deep in the saltiest water imaginable pushing Tim out of the salt slush. This is pure motorcycle death. Thankfully, we did find a carwash next to a lovely salt hotel (yes, it's all made out of salt), and spent New Year's Eve lighting off fireworks over wine and a delicious dinner we cooked up. Everything seemed perfect. The next day the bikes started up fine, and we were looking forward to heading farther south into Bolivia on a road called the Lagunas Route, passing colorful lakes of flamingoes and geological activity. But our dreams were dashed pretty quickly once our bike started stalling out while we were riding. We would start it again, go for a bit, and then stall out once more. At times it wouldn't start at all. Tim and Brendon worked on it for hours, and all the while we kept getting text messages from friends on motorcycles who had also gone out on the Salar, and now their bikes were not starting either! This all began to seem like a terrible way to start off the New Year. And then finally the bike was just dead. The Haks' bike was fine, thankfully, but we were on the side of the road, 90 miles (140 km) away from Uyuni, wondering what in the world we were going to do. So we camped there on the highest ground we could find, and tried to sleep through a night of windstorms, rain, and hail. The Haks never once left our side, and we are incredibly thankful for their patience, help, motorcycle guidance, and just plain-old moral support. I guess that's what real friends are for, and I will forever be indebted to them. Plus, they always know how to bring out a smile from even the most desperate of situations. In the morning the weather had cleared, and we stopped a motorcyclist on the road who said he had a friend with a flat-bed truck. Not excited to be towed for hours down a dirt road by a 4x4 with a rope, we figured the flat-bed would be best, no matter the price. It ended up being $145 to be driven all the way back to Uyuni where we knew there were amenities and fellow broken-down friends with their bikes. And so here we are, waiting for a homemade gasket to dry after Tim took the whole bike apart, cleaned every nook and cranny with dielectric grease, and cleaned the airbox, filters, and fuel pump. Now we just have to put it all back together again (we being Tim, and Tim being mostly Brendon Hak), and hope for the best when turning the key. Even if it does work, will it work for long, or will there need to be more cleaning and modifications done down the road? It's all just speculation at this point, but as always, we'll keep you posted. So the moral of the story is not to go out on the Salar de Uyuni in the wet season with a motorcycle, or any rustable machine I suppose, unless you are truly aware of the risks involved. Out of all our friends here at the moment, three out of four bikes did not start after driving out there. One of them is functioning again, but the other two are still in the works. The pictures we took and the experience we had of riding through the void was breathless and enchanting, but the Salar can be just as ruthless as it is beautiful. For our most up-to-minute posts and updates, follow us on Facebook and Instagram. Read about our Bolivian Adventure! |

Follow UsRide with us from Chicago to Panama!

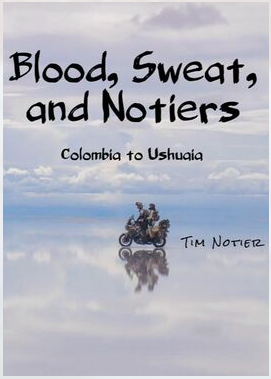

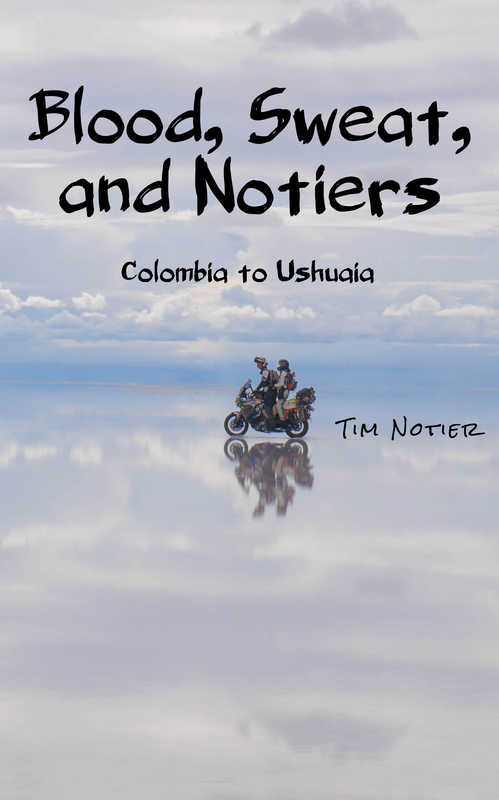

2Up and Overloaded Get inspired by the tale that started it all:

Maiden Voyage 20 author's tales of exploring the world!

The Moment Collectors Help us get 40 miles further down the road with a gallon of gas!

Become a Patron for early access to our YouTube Videos!

Subscribe to our YouTube Channel!

Subscribe to our Blog by Email

|

2Up and Overloaded

Join our clan of like-minded adventurers...

Proudly powered by Weebly

Designed by Marisa Notier